In the heart of Ontario, the establishment of a Catholic diocese in 1826 marked a turning point not just for local communities but for the entire British Empire’s approach to religious freedom. This bicentennial anniversary highlights how delicate negotiations between the Vatican and British authorities paved the way for broader Catholic emancipation.

Historical Context and Imperial Shifts

The creation of the Archdiocese of Kingston on January 27, 1826, by Pope Leo XII came after intricate discussions with the colonial office in London. This move addressed the challenges of organizing Catholic life in Upper Canada, where the absence of formal dioceses had long hindered religious practice.

Following King Henry VIII’s break with Rome, the British Crown enforced severe anti-Catholic measures, including the dissolution of monasteries, seizure of church properties, and denial of civil rights such as property ownership and public office. These policies extended to Ireland, suppressing the majority Catholic population.

After the British conquest of Quebec in 1760, King George III faced a dilemma: the French Catholic population vastly outnumbered Protestant settlers. To maintain stability and prevent alliances with restless American colonists, the Quebec Act of 1774 granted religious liberties to Catholics in the colony. This concession, viewed as an “intolerable act” by Americans, established a precedent for toleration abroad while persecution persisted at home.

A Trial for Religious Reform

By the 1820s, the strain of enforcing anti-Catholic laws in Britain and Ireland became unsustainable. The Quebec Act’s success prompted a cautious experiment: establishing a new Catholic diocese in British North America with London’s approval.

Kingston was chosen for this trial, covering vast territories including much of modern Ontario and extending toward present-day Manitoba. The initiative succeeded without major backlash, signaling that the empire could relax its three-century-old stance on Catholic persecution.

Three years later, in 1829, Catholic Emancipation legislation repealed laws denying Catholics civil rights in Britain and Ireland. This paved the way for the restoration of Catholic dioceses in England and Wales in 1850, despite initial parliamentary outrage and Queen Victoria’s reservations. Newly enacted anti-Catholic measures were never enforced, gradually eroding centuries of discrimination.

Local Celebrations and Lasting Impact

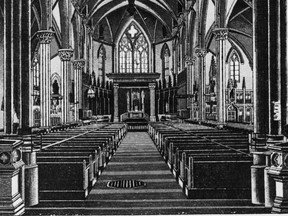

Recent bicentennial events, including a Mass led by Archbishop Michael Mulhall, underscored the diocese’s role in fostering Catholic life. The renovated St. Mary’s Cathedral in Kingston serves as a focal point for these commemorations, led by dedicated clergy.

While private prejudices lingered into the 20th century—evident in discriminatory practices in cities like London and Toronto—the 1826 decision helped cleanse the British Empire of its long-standing anti-Catholic legacy. What began as a strategic imperial adjustment evolved into a cornerstone of modern religious freedoms.