Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana, collaborates with Nakota communities to repatriate vital cultural archives containing recordings of their elders’ voices and stories.

Language Teacher Champions Full Curriculum

Kenneth Helgeson, a Nakota language teacher at Hays Lodgepole School in Fort Belknap, Montana, began his career in 2003. Elders at the school used the university’s recordings to translate stories and build an online dictionary database, with Helgeson assisting early on.

“As a young man at 19 years old, I remember being full of energy and questioning why outsiders held all this material. It belongs with our children,” Helgeson recalled. His grandmother explained that without the researchers’ efforts starting in the 1970s, these recordings might not exist today.

Helgeson learned the Nakota language from his grandmother during conversations with other elders. He shared a childhood memory: a researcher visited their home when he was 10, and his father angrily tossed the recorder, fearing the language would be stolen. “My grandmother’s foresight allowed us to hear her voice and stories generations later,” Helgeson said.

Helgeson aims to develop a comprehensive curriculum from pre-K to Grade 12, enabling full-day immersion teaching in Nakota. He marvels at a song recorded on a wax cylinder in 1914 that communities still perform at sundances today. “Our archives preserve traditions, yet our people continue living as intended,” he noted.

University Supports Data Sovereignty

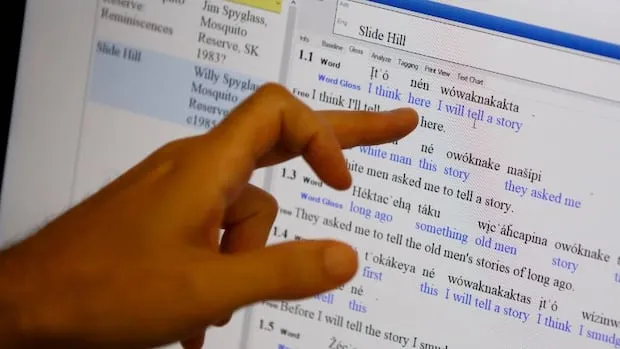

Recordings from the 1970s and 1980s have been digitized and transcribed at Indiana University. Richard Henne-Ochoa, director of the university’s Institute for Indigenous Knowledge, leads efforts to create online archives hosted by Nakota communities, ensuring data sovereignty.

“The goal is to rematriate these materials back to the Nakota communities from which they originated,” Henne-Ochoa stated. He acknowledged past academic practices, where researchers offered items like cigarettes or groceries for stories, causing unintended harm across institutions.

“Healing and relationship building remain essential,” Henne-Ochoa added. He expressed interest in partnering with Nakota communities in Canada to expand the project.

Canadian First Nation Views Archives as Relatives

Juanita McArthur, language and culture coordinator for Pheasant Rump Nakota First Nation in Saskatchewan, noted the community lost its last fluent speaker, Armand McArthur, four years ago. “We start from a blank slate in a moribund state, with no fluent male or female speakers,” she said.

McArthur described repatriating the recordings as welcoming relatives home, not reclaiming property. “We restore cultural authority, understanding these resources as shared, not owned,” she emphasized.

Upon hearing the recordings, McArthur reflected that her late father would have cherished them, as his knowledge of Nakota began reawakening before his passing. The community plans a heritage center to revive the language and culture. McArthur announced intentions for a June trip to Indiana to establish protocols and express gratitude for past stewardship while bringing ancestors’ voices home.